Edler Hawkins rose to national and international prominence in the 1960s as the first African American moderator of the United Presbyterian Church in the United States. The denomination had over 3 million members and an African American membership of less than 5%. Moderator is the highest elected office in Presbyterianism. Hawkins also worked as a member of the Central Committee of the World Council of Churches where he led global initiatives to combat racism in South Africa. He ended his career as the first African American professor at Princeton Theological Seminary.

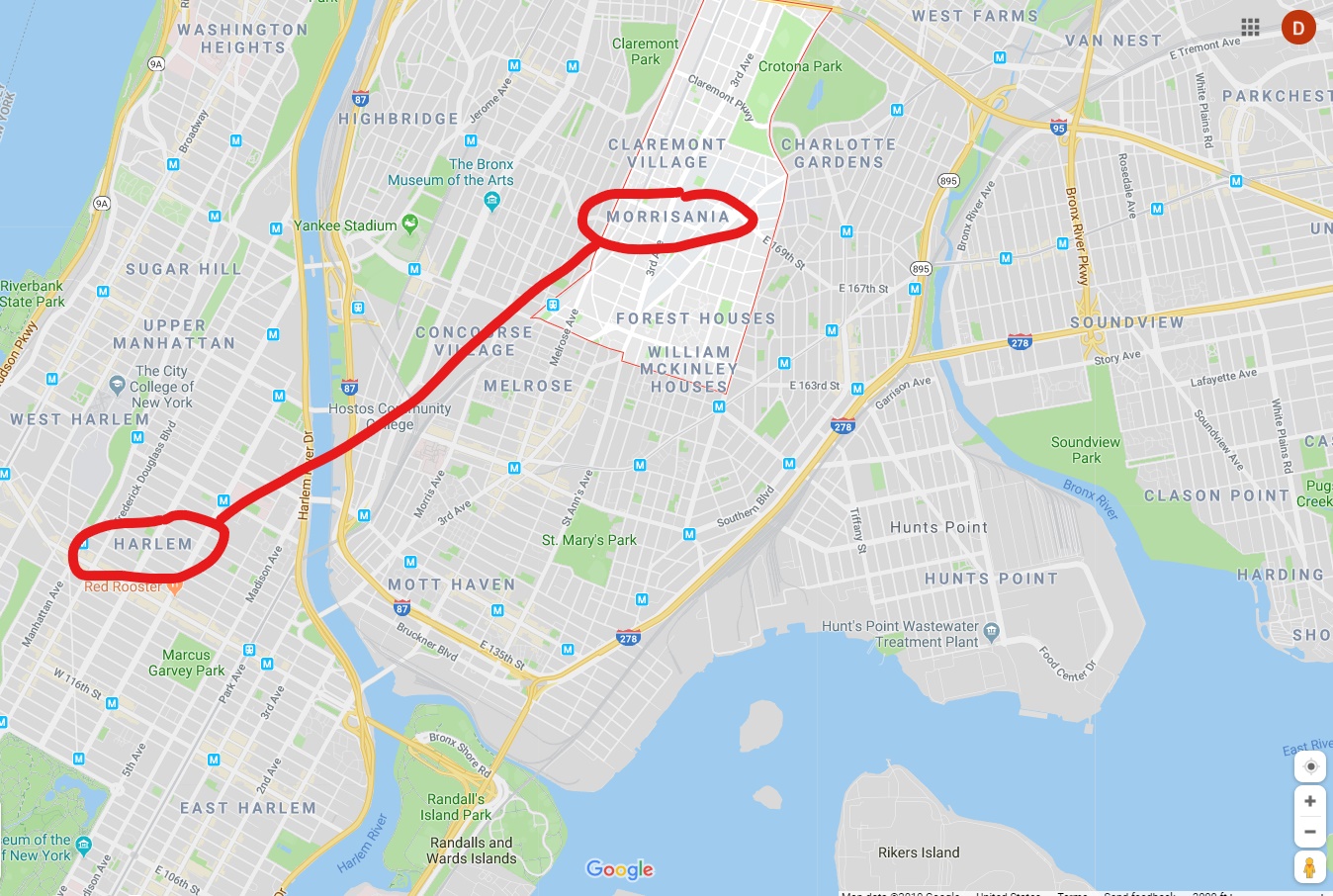

A good portion of my research thus far has dealt with Hawkins’s local New York City work. His unlikely rise to national prominence within Presbyterianism would not have been possible without his experience building St. Augustine Church in the Morrisania section of the south Bronx. Hawkins guided St. Augustine’s expansion from a handful of active members to over a 1000 by 1950. Just as Harlem provided an opportunity for Black New Yorkers to acquire better housing starting in the 1890s, Morrisania did so beginning in the 1930s. As high rent, unemployment, rampant crime, and high mortality rates afflicted Harlem by the Great Depression, an important demographic shift began to take place. From 1930 to 1970, the African American population of the Bronx grew from under 13,000 to over 350,000. By the 1950s, a broad socio-economic range of west Indians, Black southerners, ex-Harlemites, Puerto Ricans, and Jewish residents created a unique cultural dynamic in Morrisania. Varying foods, music styles, languages, fashions, and modes of worship collided within a densely populated area.

Contrary to similar examples of northern attempts at residential desegregation, these demographic shifts were not followed by immediate white flight. While whites did move away in the south Bronx, it was much more gradual than in other northern urban areas. Hawkins operated at a time in Morrisania before rampant arson, drug epidemics, and failing social structures. Public housing was sought after, schools provided opportunity, and meaningful integration had time to materialize. Preliminary evidence suggests a strong radical trade union tradition in the area may have contributed to these conditions. Also, one cannot discount the fact many residents rented their dwellings and did not share the same concerns about property values as whites in more suburban locals. I need to do waaay more research into the numbers behind the changing neighborhood demographics to back up my preliminary assertations and better visualize the rate and scale of movement taking place. Luckily, this data is relatively accessible through census records.

Before Dr. Naison’s BAAHP work, no one on the university side of things studied Hawkins and the unique African American community that arose around his church. The BAAHP allowed residents to get their story on the record. This speaks to a wider problem in the field of history concerning what gets written and what stories disappear over time. The BAAHP research forced historians in academia to consider the south Bronx multicultural community prior to 1970.

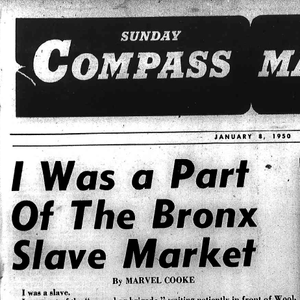

After 1938, Hawkins balanced church building efforts with more overt political endeavors. One major political initiative stands out during the first 20 years of Rev. Hawkins ministry: organizing against the Bronx “slave market.”

Labor and employment issues became apparent to Rev. Hawkins during the Great Depression and into the WWII years. Daily domestic service labor hired on a number of street corners in the neighborhoods of the south Bronx caused concern to many civic minded residents. How much were these domestic workers getting paid? What were their working conditions like? The contentious name given to this informal economy, Bronx “slave markets,” attests to the popular conception of the dehumanizing nature of the arrangement. In rain, cold, snow, and heat, women lined up along various avenues throughout the south Bronx and negotiated their domestic services.

In order to bring the issue to the attention of the city government, Hawkins helped found the Bronx Citizen’s Committee for the Improvement of Domestic Employees. The committee did not want to completely end these employment opportunities for Black women, but they hoped to improve the methods of employment. In 1939, Hawkins contacted the State Employment Department in an effort to get them to investigate the issue. The proposed solution involved establishing hiring agencies to provide a safe, protected space that could verify that employers paid fair wages.

Two years later in 1941, the New York City government entered the fray when Mayor La Guardia condemned the practice and vowed to investigate. The Mayor’s Office used methods of data collection that caused a backlash. Without consulting the Bronx Citizen’s Committee for the Improvement of Domestic Workers, a police chief and a city administrator rounded up African American domestic workers off the streets and into buses. They spent the day at social service agencies answering questions about the nature of their employment. After the Mayor’s investigation, many women feared arrest if they returned to the streets to seek work.

In April of 1941, the State Industrial Commission finally heeded Rev. Hawkins recommendation and established hiring halls for domestic workers. These hiring halls, three in all, provided a small staff that acted as hosts. The state did not involve themselves in any of the labor transactions and merely provided a physical space off the street where women could negotiate.

The African American population influx in the late 1940s and 1950s and the challenges arising from inter-racial interactions required a tenacious commitment to political activism from Rev. Hawkins. As former parishioner Avis Hanson says, “He was gentle, but he was as hard as nails. He had to be.” Hawkins also helped organize initiatives to integrate the Met-Life Parkchester Housing development, worked to ensure Morris High School maintained an equal balance of white, black, and Puerto Rican students prior to 1954, and ran for New York state office in 1950 with the strategy of uniting the Black and Puerto Rican vote. Much more work needs to be done to fully tell the story of Morrisania and Rev. Hawkins’s place within it. I’m looking forward to digging deeper.

Good read! Looking forward to learning more about Edler Hawkins.

LikeLike